Intro to Hypervisor Implants

Hypervisors are pieces of software used to manage VMs (Virtual Machines) or Guest machines on a Host machine. The main difference between a hypervisor and an emulator is that the former allows the guest machine to execute most instructions on the hardware of the host machine by translating the guest's instructions into the native machine code of the host - this provides superior performance compared to emulators, especially when it comes to tasks that are computationally intensive.

There are two main types of hypervisors:

Bare-Metal: the software is installed directly on the host hardware, bypassing the host's operating system (VMWare ESXi, KVM, MS Hyper-V, ...) So the execution order is: UEFI / BIOS → Hypervisor → OS executed by the Hypervisor

Hosted: the hypervisor runs as an application on top of a host OS (VirtualBox, VMware Workstation, ...) In this case, the execution order is: UEFI / BIOS → Host OS → Hypervisor loaded by the Host OS → Guest OS

As I lately started getting into kernel development, I ran into some posts talking about how it's possible to develop hypervisor implants - what intrigues me the most is the fact that if an attacker were to establish kernel-level access on a Windows machine with something like a kernel driver, other drivers could abuse the fact that kernel memory is shared to examine the vulnerable driver or rootkit used by the attacker. However, when it comes to Hypervisors, once the software itself is loaded into memory and it starts using the virtualization extensions for the CPU it's built for, it's virtually possible to hide any memory related to the Hypervisor from the Host OS.

This "feature" is, of course, used legitimately by solutions like Credential Guard: a security feature introduced by Microsoft to protect user credentials from theft or compromise - the products works in conjunction with hypervisors to create a secure, isolated environment for storing and processing sensitive authentication data. This is an example of VBS (Virtualization-based security). CG (Credential Guard) leverages hardware-based security features to isolate sensitive data such as "NTLM hashes, TGTs and other kinds of credentials stored applications as domain credentials".

If you want to look at how hypervisor code might look like, I highly suggest looking at SimpleVisor, its entrypoint and the wiki.

Some examples of the before-mentioned articles are:

The first thing someone might notice is that installing an additional (and malicious) hypervisor on a guest OS that is already running on an underlying hypervisor might now work as hardware only supports having one hypervisor active. This setup will still be possible as the first hypervisor will extend the support by "emulating" the hardware's functionality. This means that the first hypervisor has to be able to forward hardware instructions from the CPU to the malicious hypervisor, effectively acting as a middle-man.

With that out of the way we can start implementing a basic driver for Windows: to do that you'll have to set up your VM by installing WDK. Then you'll have to enable Test Signing mode and reboot the machine

bcdedit /debug on

bcdedit /set testsigning onSetting up a simple driver

In order to see the debug messages from the driver you will also need to open regedit, navigate to HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Session Manager and create a new Key called Debug Print Filter. Within that, add a new DWORD Value and give it the name DEFAULT and a value of 8.

You might also need to disable MS Defender and anti-tampering mode.

Now you can open Visual Studio and create a new Kernel Mode Driver, Empty (KMDF) and add the following boilerplate code (the macros.h file contains some macros for debug printing and can be found here)

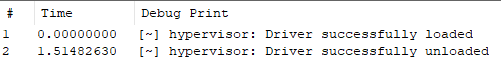

This simply defines the DriverEntry / DriverUnload functions, which are responsible for loading and unloading the driver from memory, and printing some debugging messages in the process. Now we can create the service for the driver, start it and stop it at will and we'll be able to see it load & unload from memory with a tool like DebugView.

Interacting with the CPU

Since we'll need to talk to the hardware components directly, the code we write will be brand-specific as CPUs of different brands (Intel, AMD, ...) have different register structures and instruction sets. In this case, I'm working with an Intel processor so I will be using the official Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual.

Before the driver loads into memory, we will need to perform some checks to enumerate the state of Intel's Virtualization Technology, or Intel-VTx, component. VTx is a fundamental component for any hypervisor as it allows the software to use CPU extensions for virtualization purposes so we need to check for whether the feature is enabled on the CPU. In our case, we'll focus on VMX, the Virtual Machine Monitor Extension: a specific implementation of VT-x that provides the tools and mechanisms for hypervisors to create and manage virtual machines.

Part of these properties can be also enumerated with commands like systeminfo, but if you run it on a VM you'll only get a message along the lines of

Looking at page 3925 of the manual we'll find the Discovering Support for VMX

Before system software enters into VMX operation, it must discover the presence of VMX support in the processor. System software can determine whether a processor supports VMX operation using CPUID. If

CPUID.1:ECX.VMX[bit 5] = 1, then VMX operation is supported.

So it's possible for us to enumerate the VMX state by issuing a CPUID instruction to the CPU and checking the 5th bit of the result found in the ECX register, if the bit is 1 then VMX is enabled, otherwise the feature is disabled.

What does the CPUID instruction do? Heading to page 803 we find the CPUID - CPU Identification section where the CPUID instruction is described as

Returns processor identification and feature information to the

EAX,EBX,ECX, andEDXregisters, as determined by input entered inEAX(in some cases,ECXas well).

and looking at the implementation of the instruction we see that if EAX contains 0x1 when the instruction is called, ECX will contain the VMX-related information at bit 5, just like the first paragraph mentioned (shocker, I know).

Setting up the driver for virtualization

Now we can implement this instruction in our driver, call it, and check the 5th bit of the ECX register is set to 1. The following is the complete code with the instruction implementation and the check for VMX.

Mind the @note line in the comment for the cpuid wrapper function: for most, if not all, of the functionalities we will implement there is a more "official" way of handling things by declaring a type for each register and describing its structure and the purpose of each bit like so

So if you're following along you might want to look into implementing these types and structures.

As you can see from the debug prints and the code, I made it so the driver won't load properly if VMX is not supported as it would make no sense going through with the driver entry function when the CPU we're targeting cannot be exploited.

In this case, my VM didn't have virtualization enabled so the check "fails successfully".

I'm using VirtualBox so to enable it go to Settings > System > Enable Nested VT-x/AMD-V. If the option is grayed-out, turn off the VM and execute VBoxManage modifyvm <vm_name> --nested-hw-virt on; this should select the box and allow for nested virtualization.

Another basic check we could run consists in running CPUID with EAX set to 0x0, this allows us to verify whether the CPU we're attacking is an Intel CPU; if it is the values in the EBX, EDX and ECX registers (in that order) should spell the string GenuineIntel if decoded from hex and read in LE format, this is known as the "manufacturer string".

This is the code to implement it

So we can add a simple if / else check in the DriverEntry function just like we did with the VMX check and we should get something along these lines

Now we are sure that we are working on an Intel CPU and VMX is supported so we are free to start setting up the structure for VM control: as the manual states, the hypervisor can enter VMX operation only by setting the 13th bit of the CR4 register to 1 ( CR4.VMXE[bit 13] = 1), after this is set the system enters VMX operation by executing the VMXON instruction.

VMXONis also controlled by theIA32_FEATURE_CONTROL MSR(MSRaddress3AH). ThisMSRis cleared to zero when a logical processor is reset. The relevant bits of theMSRare:

Bit 0 is the lock bit. If this bit is clear,

VMXONcauses a general-protection exception. If the lock bit is set,WRMSRto thisMSRcauses a general-protection exception; theMSRcannot be modified until a power-up reset condition. System BIOS can use this bit to provide a setup option for BIOS to disable support forVMX. To enableVMXsupport in a platform, BIOS must set bit 1, bit 2, or both (see below), as well as the lock bit.Bit 1 enables

VMXONinSMXoperation. If this bit is clear, execution ofVMXONinSMXoperation causes a general-protection exception. Attempts to set this bit on logical processors that do not support bothVMXoperation andSMXoperation cause general-protection exceptions.Bit 2 enables

VMXONoutsideSMXoperation. If this bit is clear, execution ofVMXONoutsideSMXoperation causes a general-protection exception. Attempts to set this bit on logical processors that do not supportVMXoperation cause general-protection exceptions

Since it's not the BIOS setting bits in the register, we'll have to set the lock bit and then bit 1, bit 2, or both. In this specific case we'll be operating outside SMX so we only need to set the lock bit and bit 1.

So to move on we'll need some functions to read and write values from MSR register, thankfully we can use the intrinsic functions to write a quick (and somewhat useless) wrapper

Now that we have the helper functions we can run the checks we need

Another step we need to take to prepare for the VMXON instruction is allocating what's known as a VMXON Region: a 4k-byte aligned memory area used by the CPU to support the VMX operation.

Before executing VMXON, software allocates a region of memory (called the VMXON region) that the logical processor uses to support VMX operation. The physical address of this region (the VMXON pointer) is provided in an operand to VMXON. The VMXON pointer is subject to the limitations that apply to VMCS pointers:

The VMXON pointer must be 4-KByte aligned (bits 11:0 must be zero).

The VMXON pointer must not set any bits beyond the processor’s physical-address width.

Before executing VMXON, software should write the VMCS revision identifier to the VMXON region. (Specifically, it should write the 31-bit VMCS revision identifier to bits 30:0 of the first 4 bytes of the VMXON region; bit 31 should be cleared to 0.) It need not initialize the VMXON region in any other way. Software should use a separate region for each logical processor and should not access or modify the VMXON region of a logical processor between execution of VMXON and VMXOFF on that logical processor. Doing otherwise may lead to unpredictable behavior

This process seems incredibly tedious to do in C, thankfully we can use some of the intrinsic functions the Windows API provides for the VMXON instruction (using __vmx_on()).

The VMXON region should be zeroed prior to executing VMXON, and the VMCS revision identifier written into the VMXON region at the appropriate offset.

0

Buts 31:0 VMCS revision identifier

4

VMXON data

0

Bits 30:0 VMCS revision identifier

4

VMX-abort indicator

8

VMCS data

For simplicity's sake, we’ll only be allocating a single VMXON region, and the respective VMCS region, for only one CPU core. In order to keep track of where the regions are I made a simple structure that represents the state of an individual Virtual Machine by storing the pointers for both the VMXON and VMCS regions.

This is the allocateVmxonRegion function I made to allocate the VMXON region as a continuous 4k-byte aligned memory region.

I used MmAllocateContiguousMemory to allocate the contiguous and non-paged physical memory for the region for two main reasons:

We don't have to pick a cache type for the allocated memory

The starting address of the allocated buffer is aligned by default to a memory page boundary

After we call MmAllocateContiguousMemory, the VMXON region is completely uninitialized so we have to zero it using a macro like RtlSecureZeroMemory.

The next part of the function addresses the revision identifier

Before executing VMXON, software should write the VMCS revision identifier to the VMXON region.

by reading the identifier from the IA32_VMX_BASIC_MSR register and writing it into the VMXON region; now we're ready to use the __vmx_on and checking its result: if it's 0, the operation succeeded and we can update the vmxonRegion pointer in the VM_STATE structure we defined earlier.

The last thing we will do in this post is allocating and initializing the VMCS region to complete the VM_STATE setup; the responsible code will be pretty much the same as the requirements are shared between the two memory regions, the only difference is that we'll be replacing the __vmx_on() function with the __vmx_vmptrld() intrinsic function which "Loads the pointer to the current virtual-machine control structure (VMCS) from the specified address".

This is all I'm gonna cover in this post; thanks for sticking around until the end <3

ʕ •ᴥ•ʔ

Last updated